Among the most imaginative and multifaceted designers of the 20th century, Bruno Munari (Milan, 1907 - 1998) is one of the rare masters who was able to leave his mark in the history of art, design and graphics, escaping from any kind of classification. In his uninterrupted research between different disciplines, Munari devoted himself to painting, sculpture, architecture, photography and books, becoming known above all for his didactic-creative activity dedicated to children.

Not surprisingly, defined by the French art critic Pierre Restany "the Leonardo and the Peter Pan of Italian design", Munari used to say that as a child, not having many toys available, he built them himself, replicating things, and sometimes inventing things. His dedication to the childhood sphere is expressed in the workshops he made for children in schools and museums all over the world, as well as in his educational games, such as the folding structures, the objects to assemble, the musical instruments and the books involving children in the world of shapes and sounds.

From graphics to design, Munari embodies a contemporary taste that rediscovers a multidisciplinary attitude in the creative process, employed by a few 20th century "outsider masters" who changed the history of design, and whose work does not go out of fashion. Even if we could not really define him as an outsider — his projects are nowadays more celebrated than ever and his rarest pieces reach remarkable prices at auctions — Munari has carried out a reflection on design that frees itself from the idea of globalization, a thought that surely encountered the uncertainties and the difficulties faced by designers who fight for their ideals.

Munari’s first flash of inspiration was the futurist work of Fortunato Depero and Giacomo Balla, from whose observation he gave life to his Useless Machines (1933), shapes that he cut and suspended through moving threads in order for them to change their perception in space. To inspire the shapes and volumes that Munari adopted in his projects were also the simplicity of the Bauhaus geometries, and the Japanese thought at the basis of the art of origami, suggestions that are to found in his Illegible Books, born from cut and folded sheets of paper organized in compositions that can change according to the reader's will.

The stylistic code behind Munari's objectsseems to rely on a balance between technique and spontaneity, seriousness and playful aspect, which is the result of a finely studied planning. Think of his Cube ashtray: in the mid-50s, after meeting Bruno Danese and Jaquelin Vodoz, the pillars of the Danese household items brand, Bruno Munari proposed to the company to make this ashtray: it was a failure, but Danese continued to produce it. Over time, Cubo became a best seller of the company, as well as the pencil holders or the iconic Falkland lamp by Munari did: all design classics, all still in production and appreciated for their aesthetics, which balances simplicity, elegance and function, surviving the change of fashions. The creative partnership between Danese and Munari was the forge of a series of objects suspended between art and design that helped to shape the brand's identity.

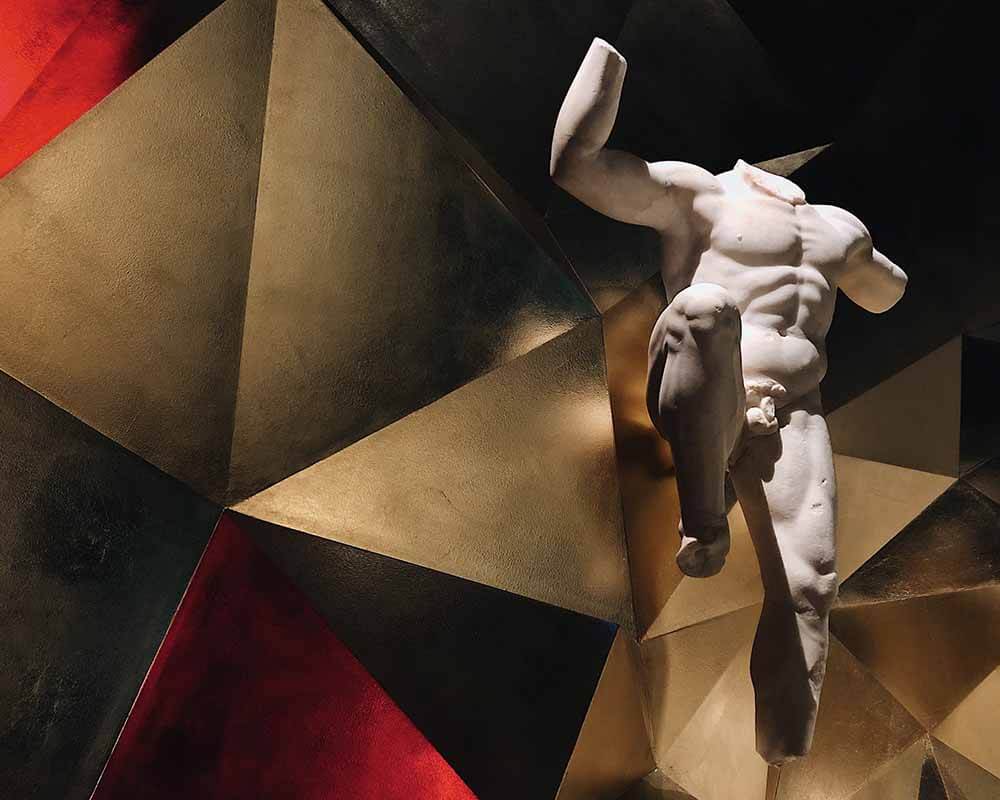

When talking about Bruno Munari, the "objects between art and design" topic always arises. For example, by looking at Munari's recent creations, such as the pierced screen designed for Zanotta in 1989, we find out it derives from the much earlier Travel Sculptures series, which Munari created at the end of the 50s (some of them appear in the photo): made of wood, metal, plastic or simple cut outs of paper, they somehow escape classifications, depending on how they are looked at or used: are the largest ones environmental art works? Are they sculptures? Are they functional pieces? They are indeed all of these things, but they can also become conceptual pieces of furniture, fixed and sometimes moving: as the designer explained, «they have the function of creating, in an anonymous hotel room or in an environment where you are hosted, a point of reference where the eye finds a link with the world of one's own culture»

.png)